A trade so obvious even the U.S. gov. can see it…

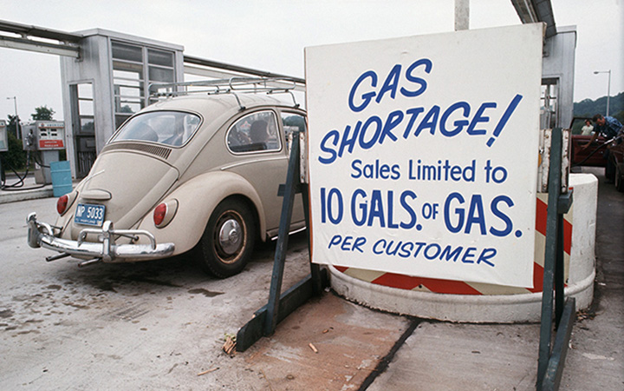

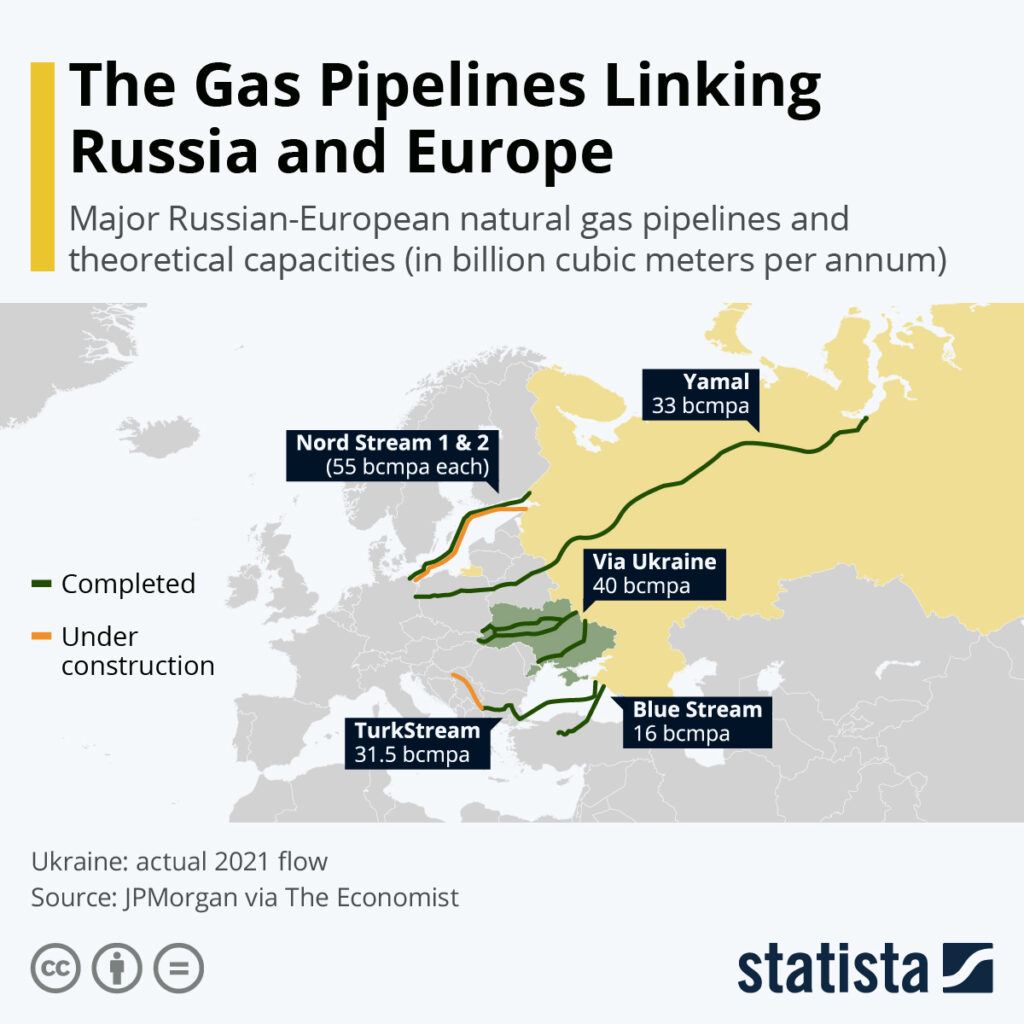

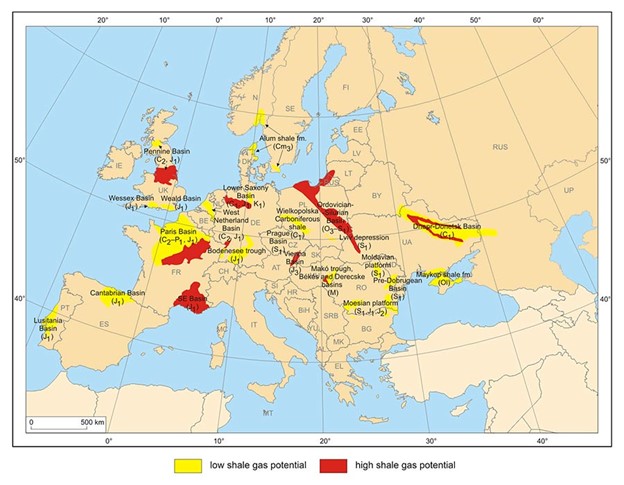

When Russia turned the nat gas taps off things got ugly.

Europeans saw their energy bills go from €250/month to more than €2,500/month.

Energy costs skyrocketed from under €100 / MWh to +€1,000 / MWh in some EU countries.

Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) import prices shot up from €7 in 2021 to €70.

Corporations, individuals, and utilities felt the pain.

To ensure that there would be enough natural gas to keep the lights on, many fertilizer companies were forced to cut production by 50%. The effect on crop yields are still to be seen.

Then, there was relief.

It’s better to be lucky than smart…

Europe got lucky, and had the second mildest winter on record – which brought energy prices down to pre-invasion levels.

A blessing for European energy bills and an opportunity for savvy investors.

This wasn’t a stay of execution… just a delay. However, it has given the West more time to come up with solutions – one of which is U.S. LNG imports.

The Freeport LNG terminal, which was shut down due to a fire and explosion in June of 2022, is ready to come back online. This will be a major source of LNG exports heading to Europe.

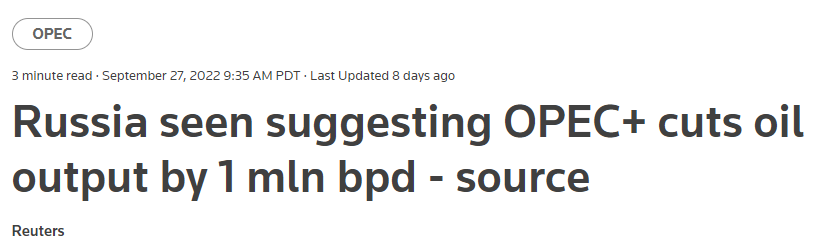

Added EU demand will put price pressure on U.S. natural gas.

There is a high probability that a significant price move could occur in the North American natural gas markets over the next 12 months.

Last summer we saw U.S. natural gas prices break $7.00 / mcf for the first time in 14 years.

State of the (natural gas) Union.

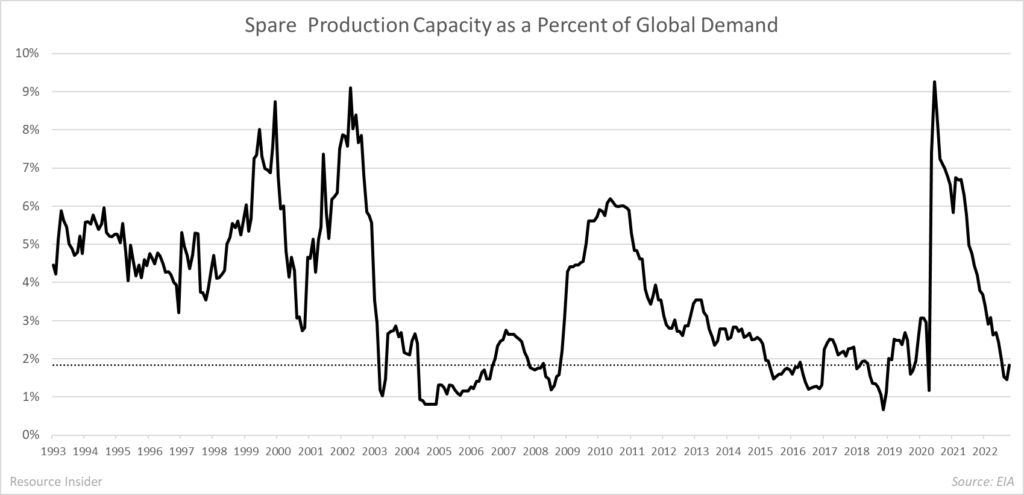

We have been convinced that U.S. oil and gas production growth would stall and eventually turn negative, delivering a major hit to US energy supply. This thesis has been largely driven by the research of our friend Scott Lapierre – a world class petrophysicist that we had on the Ri Podcast 3 years ago.

So far, things are playing out as we expected.

Peak Oil

Today many analysts refer to peak oil demand, but originally peak oil referred to supply.

The idea of a basin’s peak oil supply is associated with a controversial Royal Dutch Shell geologist from the 1950s named M. King Hubbert. He believed that an oil or gas field’s production resembles a bell-shaped curve.

Hubbert expected a field’s production to increase at an accelerating rate, level off / plateau, and then decline at a rate similar to its growth phase.

In 1956 he predicted that U.S. crude oil production would peak in the 1970s at around 10 mm b/d. In 1970 when U.S. production did peak at 10 mm b/d, his work gained widespread attention.

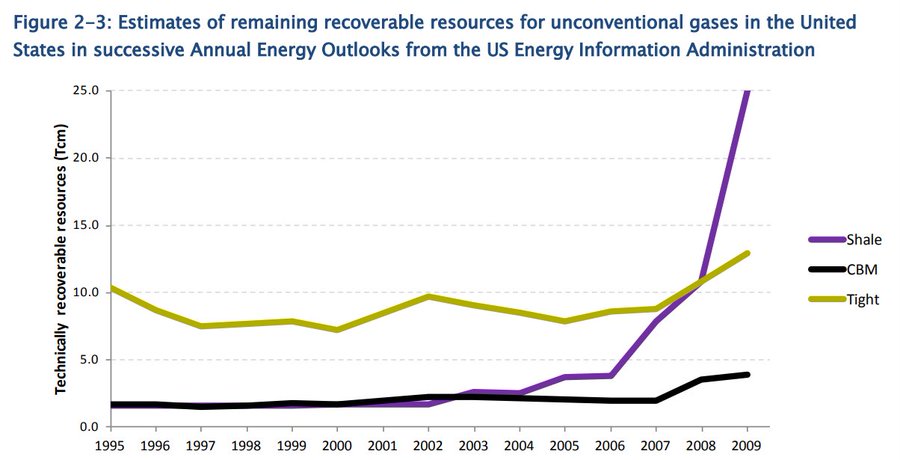

From 1970 until 2008 U.S. oil production declined, until a new type of basin came into the limelight…

U.S. Shale Oil & Gas

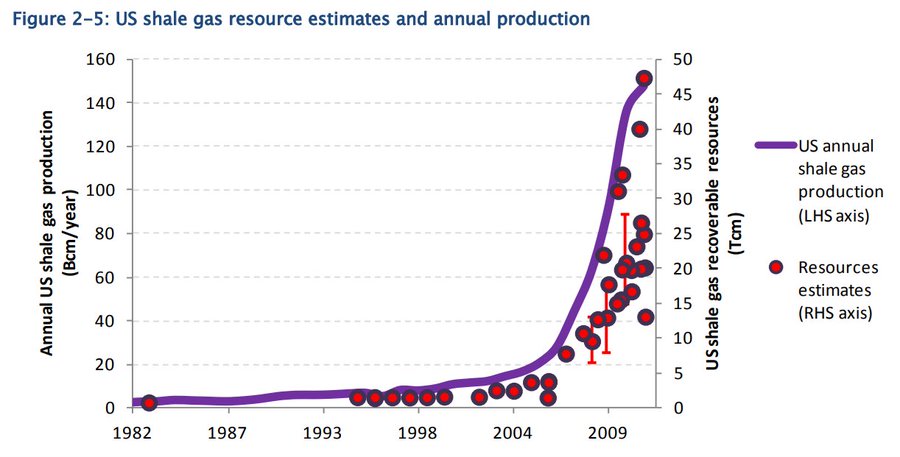

When hydraulic fracturing (aka: fracking) came on the scene, shale oil and gas became huge. In return, the U.S. became the largest producer of oil and gas in the world.

But, we believe the theory of a bell shaped production curve still holds true for fracked wells, just like it did for conventional oil and gas.

If we’re right… We’re running out of O&G.

Our own controversial geologist, Scott Lapierre, has been pounding the table warning investors of declining shale production.

Scott came to this conclusion independently of Hubbert’s ideas. Scott’s ideas arose from first principle calculations using the physical properties of oil, gas, and the rocks that trap it.

If both Scott’s science and Hubbert’s theories are correct, it could mean U.S. oil and gas production could fall as fast as it rose since the onset of fracking.

The proof is in the pudding.

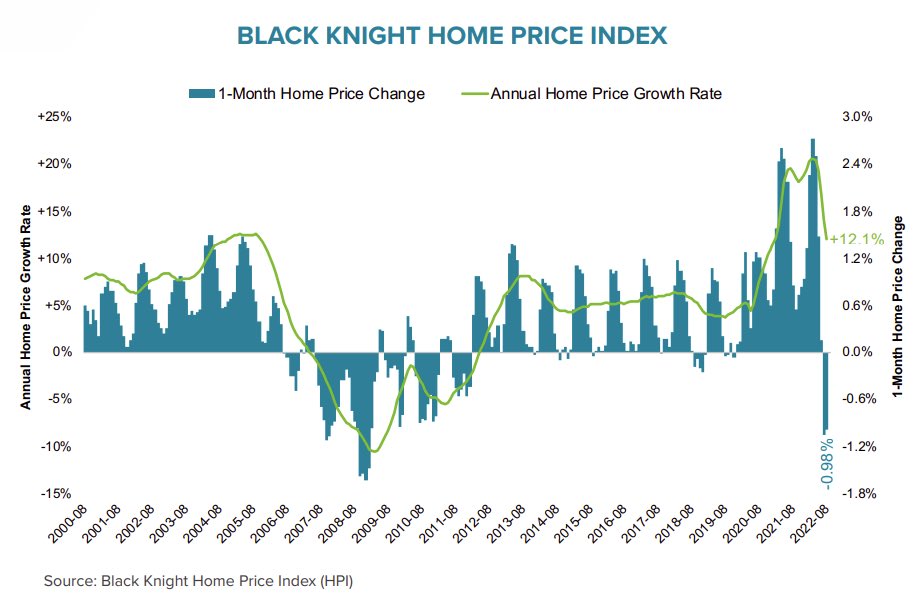

The two earliest shale basins, the Barnett and Fayetteville, saw peak production between 2011 and 2014. Since, they have each declined by 70%.

Both of these early shale basins were gas fields.

What does this mean?

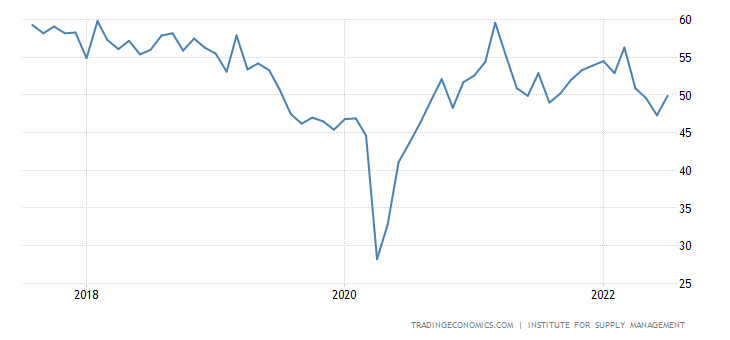

The days of cheap natural gas in the U.S. are over.

The next largest natural gas fields are the Marcellus and the Haynesville.

The Marcellus is following Hubbert’s bell curve model, having reached its plateau in 2020. Over the last twelve months, the Marcellus declined by 300 mcf/d. Hubbert models suggest that the Haynesville could plateau as soon as next year.

Exploration is dead.

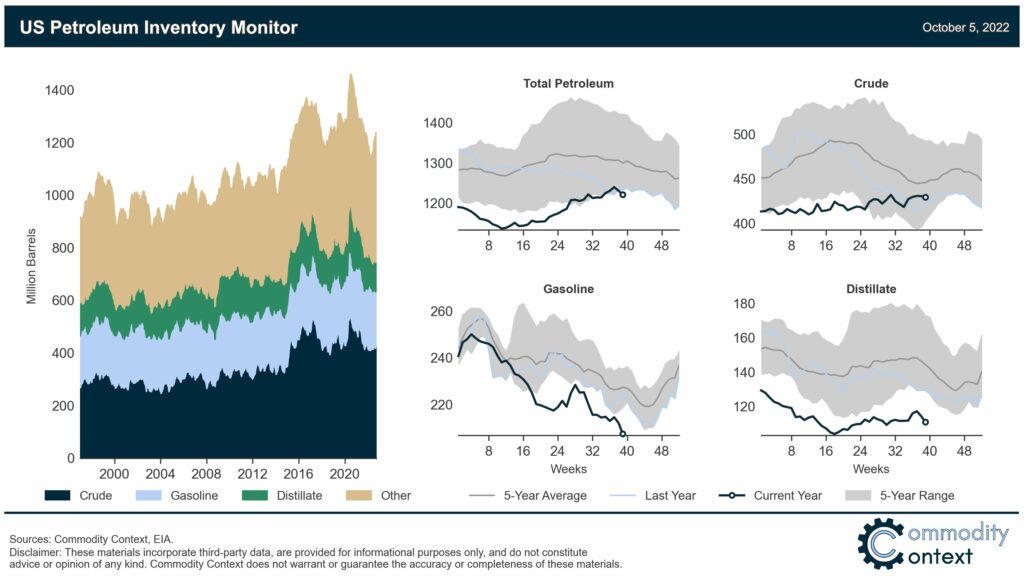

Natural gas drilling in the U.S. is near all-time lows.

The number of active natural gas rigs in the United States has declined by more than 75% since 2014, resulting in U.S. gas production declining by more than 10% in the same period.

Because of low energy prices, and a move towards clean energy, the appetite for hydrocarbon exploration has been dead.

This leaves the U.S. in a precarious position… And natural gas prices are vulnerable to a surge.

We’ve been watching the U.S. energy sector for 3-years, searching for the right deals to get energy exposure through natural gas.

On a trip to Texas earlier this year, we finalized one of our next deals…

Project Patriot

This is a natural gas development opportunity in East Texas with an all-star team.

The company is led by a gentleman that was groomed at a multi-billion dollar oil and gas company before he left to run his own deals. After a string of success stories, he is putting together his forth deal.

On the technical side, this company is led by the geologist that literally wrote the discovery paper for the Haynesville-Bossier shale basin, where this deal is located. With her protege, she’s successfully drilled over 100 wells in the basin.

Now, they’re at it again.

Jamie Keech

CIO; Editor

Nick D'Onofrio

Head of Research